Part One: Gatekeepers and Why I’m Against Them

I hate gatekeepers. That’s the long and the short of it. Maybe it’s because I come from a working class family and I all-too-often encountered people who stood in the way of my curiosity and opportunities. Maybe it’s because I made my career in the theater, a place overrun with gatekeepers. I don’t know. All I know is that I’ve always resented gatekeepers.

First, some definitions: what is a Gatekeeper? (In Part 2, I will define a Critic and how the two differ, and why I love love love critics.)

A gatekeeper is someone who controls access to something or has the authority to allow or deny entry. In the theater, gatekeepers are most active PRE-artwork or PRE-career. Gatekeepers decide whose play gets produced, who gets admitted to prestigious training programs, who gets cast or hired, who is allowed in the union.

Agents are gatekeepers, as are casting directors, directors (been there), producers, literary managers, executive and artistic directors, university admissions office staff, faculty members (guilty as charged), and so forth. It sometimes seems as if most books that are written about theater and film are about how to get a gatekeeper to work FOR you instead of against you; how to convince the gatekeepers to let you in. A Chorus Line is an entire musical about gatekeepers.

Gatekeepers operate from an attitude of scarcity: I have a certain number of students I can accept, plays I can schedule, roles I can fill, clients I can handle. And of course, there are way more people available than can be used. But like the rest of the US culture, the supply of people with talent is not evenly distributed. It tends to be concentrated in a few big cities that hoard the opportunities, and in that respect the geography of theater itself is a gatekeeper: some people simply can’t afford to move to one of these cities. I want to be clear: there’s nothing intrinsically nefarious about this. Gatekeepers are not villains—some are, but most aren’t. Rather, they operate in a system where there is vastly more supply of talent than demand for it.

But the effects of gatekeepers can be problematic. Their individual preferences, conscious or unconscious, necessarily lead to certain choices, and when those choices are shared by many other gatekeepers, the result is homogeneity and safety. This safety is magnified when there is a great deal of money at stake. Still, we have become too sanguine of gatekeepers in theater.

A quick analogy from the world of classical music might efficiently explain the effect of gatekeeper prejudices. In the 1970s and 1980s, symphony orchestras began conducting blind auditions to address concerns about bias and promote fairness in the selection process. Before blind auditions, musicians were often selected based on factors unrelated to their musical abilities, such as gender, race, or personal connections. So screens were introduced as a means of reducing these biases, and by putting a literal barrier between the musician and those hiring them, it forced judges to focus solely on the quality of the musicianship. This has contributed to a more inclusive and merit-based selection process in the classical music world.

Obviously, in theater blind auditions are totally impractical because facial expression, gestures, and vocal quality are part of the decision-making process. (It would, however, be interesting to explore whether some version of blind auditions might be effective in the case of directors or designers. One also wonders whether there is evidence of greater diversity in casting, say, in the hiring of actors to voice animated characters (are they blind auditions?), or what effect something as simple as withholding resumes until after callbacks might have, so that casting agents and directors aren’t swayed by credentials. But I digress.)

Casting is particularly prone to reflect the effects of societal norms and individual preferences regarding height, weight, race, age, gender, physical ability, attractiveness, vocal quality, and so forth. Similarly, the plays that are chosen for production reflect gatekeeper judgments regarding the structure and content of plays and whose stories are judged worthy of production. How many artists never get a chance to share their work because they don’t match some preconception in the mind of a gatekeeper.

Let me illustrate this with a story. I got my Masters Degree from Illinois State, and later I went back there to teach and work as an administrator. The theater department at Illinois State is where a lot of people were trained who went on to have illustrious careers in theater and film: Gary Cole, Laurie Metcalf, Gary Sinise, Judith Ivey, Jane Lynch, Terry Kinney, Moira Harris and many others. Including John Malkovich. The story was that, during his entire time at Illinois State (he didn’t actually graduate because when he failed to meet the final graduation requirement: passing an exam on the Illinois Constitution. When he arrived to take the exam, he decided that room was too hot, and walked out)—during his entire time at Illinois State, he got cast in ONE mainstage role: the guy who delivers the ant farm in The Man Who Came to Dinner. I believe that role has one line. The gatekeepers on the faculty thought he was too weird to cast or something (although that didn’t stop them from later displaying a massive photograph in the lobby of him delivering said ant farm in said production.)

But here’s why that didn’t matter. The department had a very active “freestage” program in which anybody who wanted to do a play could reserve one of the classrooms when it wasn’t being used and put on a performance. There was a legendary production of David Mamet’s American Buffalo performed in the prop storage room to only a handful of people at a time, for instance. Malkovich, along with his future Steppenwolf co-founders, were busy creating, with no budget, freestage production after freestage production in classrooms of plays they wanted to do, a process that doubtless gave them the skills to do the same thing in the basement of a suburban Chicago church where they were discovered by Tribune theater critic Richard Christianson.

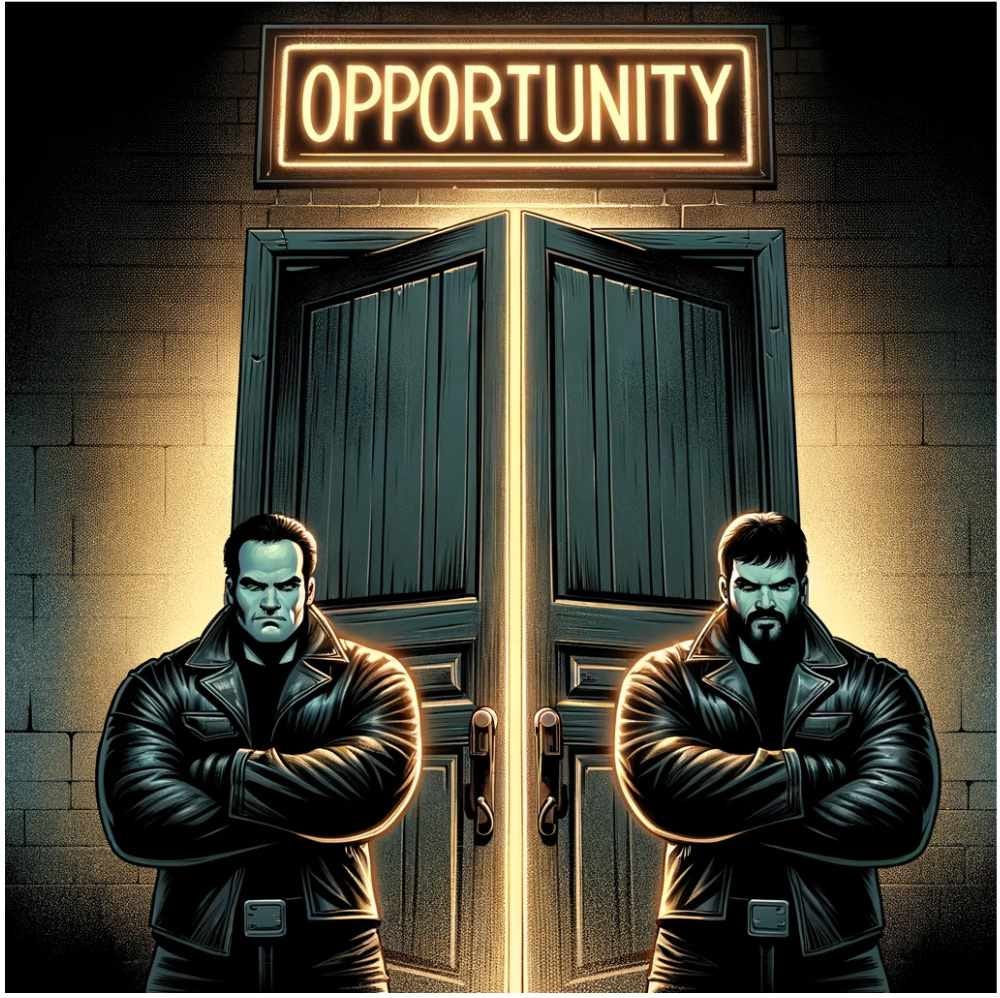

Malkovich and many, many others thereafter saw an open door marked Opportunity that had no gatekeepers preventing them from following their passions and they walked right through it.

My goal, in books like DIY Theater MFA and Building a Sustainable Theater, has been to reduce or eliminate as many gatekeepers as possible for individual theater artists. (Indeed, the subtitle to the latter book is “How to Remove Gatekeepers and Take Control of Your Artistic Career.”) Part of that requires dismantling the mythology of the theatrical hierarchy that says only certain theatrical work is considered worthwhile.

I have often quoted Seth Godin’s book The Icarus Deception: How High Will You Fly? in order to illustrate the negative effect of gatekeepers.

“Sarah loves to perform musical theater. She loves the energy of being onstage, the flow of being in the moment, the frisson of feeling the rest of the troupe in sync as she moves. And yet . . . And yet Sarah spends 98 percent of her time trying to be picked. She goes to casting calls, sends out head shots, follows every lead. And then she deals with the heartbreak of rejection, of being hassled or seeing her skills disrespected. All so she can be in front of the right audience. Which audience is the right one? The audience of critics and theatergoers and the rest of the authorities. After all, that’s what musical theater is. Its pinnacle is at City Center and on Broadway, and if she’s lucky, Ben Brantley from the Times will be there and Baryshnikov will be in the audience and the reviewers will like her show and she might even get mentioned. All so she can do it again.

This is her agent’s dream and the casting agency’s dream and the director’s dream and the theater owner’s dream and the producer’s dream. It’s a dream that gives money to those who want to put on the next show and gives power to the professionals who can give the nod and, yes, pick someone.”

Godin continues:

“But wait. Sarah’s joy is in the dance. It’s in the moment. Her joy is in creating flow. Strip away all the cruft and what we see is that virtually none of the demeaning work she does to be picked is necessary. What if she performs for the “wrong” audience? What if she follows Banksy’s lead and takes her art to the street? What if she performs in classrooms or prisons or for some (sorry to use air quotes here) “lesser” audience? Who decided that a performance in alternative venues for alternative audiences wasn’t legitimate dance, couldn’t be real art, didn’t create as much joy, wasn’t as real? Who decided that Sarah couldn’t be an impresario and pick herself?

The people who pick decided that.”

(The working title for Building a Sustainable Theater was Pick Yourself, but I changed it because I shuddered to think what Google search results would look like.)

Other art forms have taken advantage of the throwing open of the Opportunity Gates by the internet, which operates in an environment of abundance—there is almost unlimited access to the means of production, and a seemingly unlimited amount of storage. One result of this phenomenon is that there are far fewer gatekeepers: if you want to write articles, you sign up for Substack or start a blog; if you want to publish a book, you sign up for Draft2Digital or Kindle Direct Publishing; if you want to perform your music, you make a video and upload it to YouTube or Vimeo; if you want to talk about things that interest you, you create a podcast; if you want to make cosplay costumes or jewelry, you open an Etsy store. You may have to pay a little for web hosting, but that’s really the only barrier. You don’t have to ask permission from a gatekeeper to do what you want, and nobody can say you nay.

Theater, unlike the internet, operates in an environment of scarcity—the means of production are controlled by a small number of people. The sense of scarcity is magnified through the creation of a steep hierarchy in which certain places, programs, or theaters are seen as being more prestigious than others. This hierarchical model of scarcity is then internalized by theater artists, who learn that there is only one Door of Opportunity, and to get through it you have to navigate an army of gatekeepers. And they forget all about Freestage.

Don’t forget about Freestage.

Housekeeping

It’s been too long since I last wrote something. January slipped away from me between illness (nothing major) and other projects.

Other Projects

I have created an eBook and a paperback version of DIY Theater MFA: Growing Your Theater Skills When You Don’t Have the Time, Money, or Opportunity to Pursue a Graduate Degree. I have done absolutely nothing yet to promote it, so if you have anybody you know who might be interested, I hope you’ll pass along the link. The free online version remains available as well, which would allow people to sample the book.

I’m also in the early stages of creating an Author Page, which will gather together all my writing in one place. I’ll let you know when that’s available, but the URL will be scottwaltersauthor.com.

The draft of the HowlRound interview about Building a Sustainable Theater is currently with the editor. It isn’t a done deal that they will publish it, but if they do, I’ll let y’all know.

Speaking of editors, my editor at Waveland Press has decided we ought to do a 3rd edition of Introduction to Play Analysis. It’s possible that I may be merging it with my book Play Analysis in Action: Susan Glaspell’s Trifles, but we’ll see how it plays out.

So I haven’t been laying around taking antibiotics and eating saltwater taffy all last month…although I did take some antibiotics, and I have discovered the best saltwater taffy I’ve ever eaten at Taffy Town — highly recommended.

As usual, I concur with your observations. I've run into a recent string of gatekeepers for the first time ever. But, then "times-they-are a-changin'."

Recently, every theatrical literary manager I've had contact with regarding submissions, has been female, most ethnic and some LGBTQ. As you may guess, I am none of those things. Some of these gatekeepers blatantly publish a desire or preference for submission that is specifically play subjects regarding females, or of racial or LGBTQ issues- or from exclusively writers who are one or more of these things. And I add, everyone of them is a playwright themselves, seeking opportunity for themselves. (Usually providing them one new premiere of their own work every 1-3 years.)

Furthermore, if you look at the submitted play selections they make, even when they do not advertise this bias, it is exactly this; plays on the experiences of women, ethnic experience or experiences of the LGBTQ community.

I get it, really. After decades of what must be a presumed bias in theater, I guess the assumption that play selection favored straight, white-only male writers, these women are practicing a long needed balancing act of reverse discrimination to provide much needed opportunity to a previously excluded and disenfranchised group of writers. And it doesn't matter that at age 70, with my submissions, they practice ageism too.

I was at first incensed that they would practice this reverse discrimination, I assumed well-educated gatekeepers like these would look past that and judge material by it's quality. But, then I realized that most have little education or experience to make such quality judgement. (Kind of like most Broadway producers.) None have spent decades practicing, learning from mistakes and honing craft. Most are merely diploma-based students struggling to find opportunity for their own works while earning a wage controlling the gate to favor their preferences..

Well, these things tend to bounce back, in cycles. Already there is good evidence that these preferential selections are losing audience base, the majority of annual member-patrons not identifying with the subject matter and growing weary of the social-political rebuke and task-taking these often angry diatribes blatantly attempt to foist upon them. Audiences in Portland and Ashland have voiced weariness to this persistent onslaught of programming. (And no, this was not discriminatory rhetoric, but the reaction to programming fatigue.)

And then they wonder why their companies are bleeding out money and going into bankruptcy. Simply stated, they put their bias agenda ahead of the program desires of their market audiences.

Well, this is, indeed, the flavor of the month. I am happy for new voices to be heard, a little less so by this discrimination. I give these gatekeepers much kudos. It used to be that those who can't write (achieve opportunity and success) would teach. (And most still do.) But, now, a subset simply take control of the company to see opportunity is theirs to take and bestow on their favorites. Brilliant!

Were I playwright more than composer, I would be moved to write the perfect Geo S. Kaufman satire this situation suggests: the travails of a playwright intentionally writing and submitting a fictional history play that hits every cliche of these preferential demands and then forced to pretend to be a disenfranchised playwright selected to see a production of the selected work through. (Or maybe lop off the latter part and just submit the work under a female, gay, ethnic nom-de-plume.) Oh, well, I will accept partnership offers, as composer, if this idea warrants becoming a musical. Ha!