One of the chapters in Cal Priner’s and my book Introduction to Play Analysis is about the Theatrical Contract, an idea that Cal spelled out in a long-forgotten essay he published early in his career, but which he shared with me back when I was a student at Illinois State. A theatrical contract basically describes the “rules” of the world of the play: does any character explicitly acknowledge the presence of the audience, and if so which character(s)? (In the case of Wayne’s World, this rule is made explicit!) Do characters speak in verse, or burst into song? Can characters fly? Do individual elements of the scenery, costumes, lighting, sound reflect normal lived reality, or are there distortions or exaggerations? The play doesn’t spell out the Theatrical Contract explicitly, but usually in the first 10-15 minutes the rules of the world are implicitly made clear to the audience.

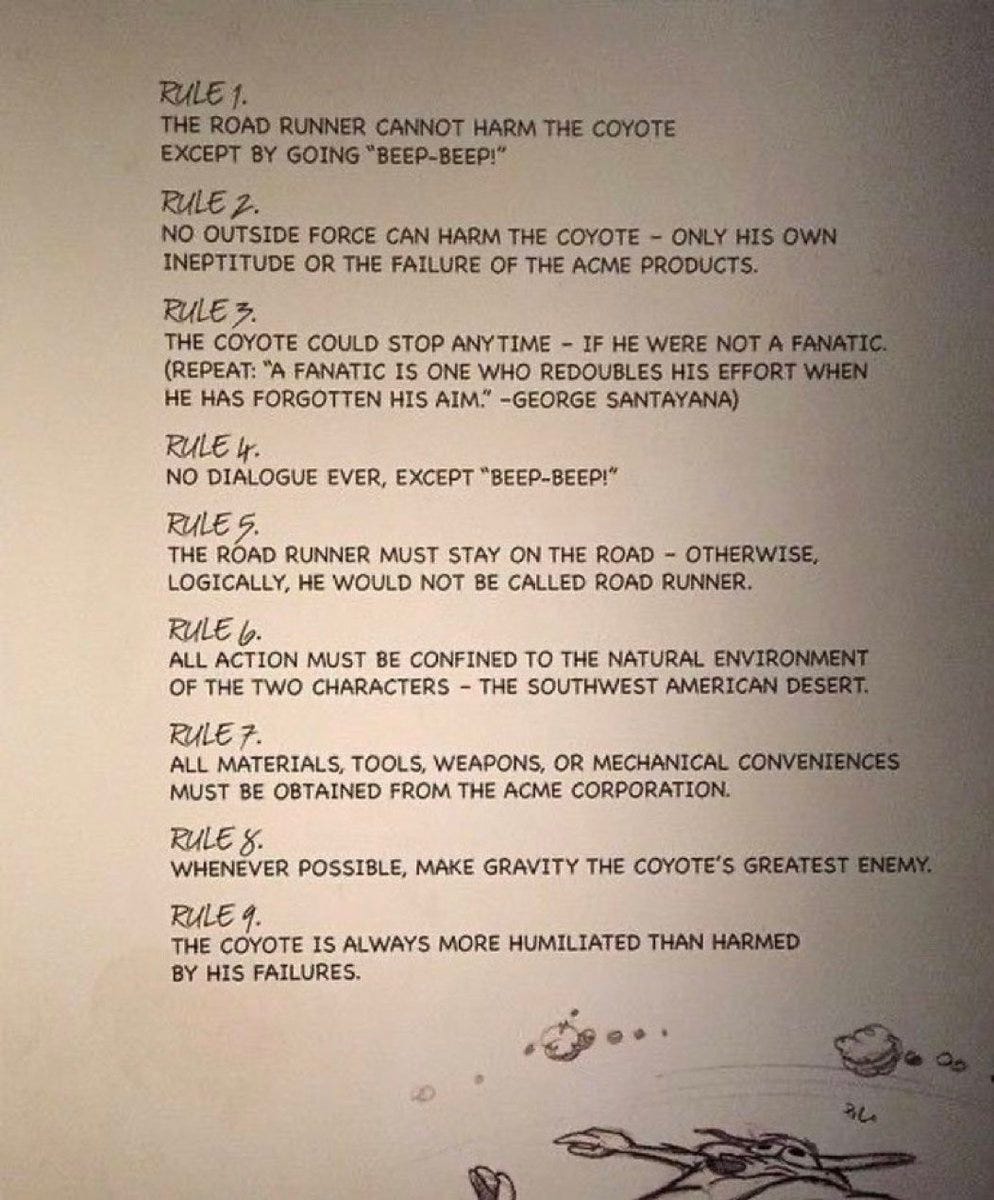

A couple days ago in my Twitter feed, there appeared a perfect example of a Theatrical Contract made explicit in a section of Chuck Jones’ book Chuck Amuck: The Life and Times of an Animated Cartoonist. Jones indicated that the animators associated with the Roadrunner/Wile E. Coyote cartoons closely followed ‘The 9 Rules For All Roadrunner And Wile E. Coyote Interactions.’ Here is an image from the book:

It’s such a perfect rendering of a Theatrical Contract, I almost cheered (maybe I’ll include it in the next edition of the book)! What’s particularly interesting is Rule #4: “No dialogue ever, except “Beep-beep!” This rule was strictly followed in the Road Runner cartoons, but some of you may remember that Wile E. Coyote also appeared in cartoons with Bugs Bunny, and in those films he does speak, and in a high-toned dialect to boot (thank you, Mel Blanc)! It’s possible that the key to Wile E’s speech might reflect the nature of the protagonists in the two cartoon series: the Roadrunner couldn’t speak; Bugs Bunny never stopped! [By the way, I suspect these “rules” developed over time, and weren’t explicit when the first Road Runner cartoons were being created. Play analysis techniques are most useful in understanding a text thatr already exists, and less so when writing a new one from scratch.]

Since many people worked on these cartoons, this list communicated to the creative staff the guidelines to follow as they created new cartoons. It’s sort of like a “style sheet” at a publication like the New York Times or New Yorker, which describes the way certain aspects of the writing are handled (e.g., at the Times, the first time a person is mentioned, they are referred to by their full name, but thereafter they are called Mr. ____ or Ms. _____).

This kind of understanding is equally important for effective communication between members of a play’s creative team. All of the artists involved in bring to life a production need to know what story is being told (the conflict structure) and how the story is going to be told (the theatrical contract). Otherwise, they can find themselves working at cross-purposes.

The problem is that there often is not a common “language” shared by an artistic team, which can slow things down while each artist tries to understand how other members of the team communicate. The language of acting is filled with such potholes: terms that mean one thing in Theory A, and something different in Theory B., which can lead to confusion in the rehearsal room. Cal and I ran into this when we were writing the chapter on Conflict at the Level of the Scene. In one draft, Cal addressed this directly, because I kept focusing on “moments” whereas he wanted to be more conflict-oriented:

Theater literature isn't consistent in its treatment of terms that are central to communication about our work, and this includes such terms as "beats" and "actions." Realizing that you will encounter various definitions, lets's think of a beat as a moment in which a character tries to satisfy an absence she is experiencing. And, let's think of an action as the activity that she pursues in an effort to satisfy the absence.

We dumped my fuzzy use of the term “moment,” and went with “action” and “beat,” and the book was better for it.

This is one reason I feel so strongly about the value of an ongoing company. Once artists develop a shared language, their communication becomes so much more efficient. Many long-term partners refer to developing a “shorthand” that, when added to a relationship of trust, allows artists to go further and deeper in their creative exploration.

In lieu of such shared experience, I wonder whether it might be useful for new collaborators to discuss their own “style sheet” up front, so everybody is on the same page. Time is so short in rehearsal, and it might be useful to get beyond the Tower of Babel that can result when worlds collide.