I’m excited to finally get a chance to share my thoughts about Italian Nobel Prize-winning playwright Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author. I’m also a little daunted: yesterday, I spent 90 minutes trying to get started, and I ended up with two paragraphs that sounded like they were written by a first-tear grad student trying to impress the professor. Today, I’m just going to be straightforward.

I think it’s easy to read this play, or watch the PBS version (starring a surprisingly fantastic Andy Griffith as the Father, and come away intrigued but not quite sure what the point was. It is what is called a “metatheatrical” play, a fancy way of saying it is a play about a play, and plays of that nature have a tendency to be about the “nature of reality”—what’s real, what’s an image, what’s a mask. Six Characters is no exception.

I want to discuss this play from two perspectives, which I will call the “vertical plot” and the “horizontal plot.” Understanding the vertical helps to illuminate the horizontal plot, so I will start there.

Vertical Plot

The vertical plot is about a company of actors and a director who are about to begin a rehearsal of a play that none of them like that is by a playwright named Luigi Pirandello. Just before they get started, however, they are interrupted by the arrival of the titular “six characters”—a family comprised of a father, a mother, an adult son, an adult stepdaughter, a 14-year old boy, and a 4-year old girl. They announce that they are characters who were created by a playwright who had abandoned them because he was “unable or unwilling” to figure out how to use them in a play. They are in “search of an author” to tell their story and allow them to “live.” The first act concerns their attempt to persuade the company to allow them to be their next production, and the next two acts are their attempts to stage their story using the actors of the troupe (to hilarity of the characters, who find their performances ridiculous).

For the moment, I want to put the characters “behind my back,” as it were, and focus on the theatrical contract, which you may remember from my discussion of Cormac McCarthy’s The Sunset Limited are the “rules of the world of the play” that are established by the playwright: does anybody directly acknowledge the presence of the audience? and are their any elements of the play that are not “realistic,” meaning not reflecting our everyday experience of life, but rather have at least some elements that are distorted or exaggerated (for instance, characters speaking in verse or bursting into song would indicate a nonrealistic contract; characters who can fly; light cues that lower the surrounding lights while bringing up a single spotlight; and so forth).

Pirandello goes out of his way to establish not only a realistic contract, but a hyper-realistic one in which there is a one-to-one correspondence between the world of the play and the world of the audience: the theater we’re in is the theater where the rehearsal takes place; the actors are played by actors; the director is often played by a director (John Houseman, in the Andy Griffith version); there is a stage hand who appears, who is often played by someone on the stage crew; the director and actors walk down the aisles, confer at the edge of the stage, and a few enter from the front of house. This hyper-realism encompasses the element of time as well: a minute within the story is the equivalent of a minute in real life. Indeed, even the intermissions are justified within the play’s action: the first takes place during a called break when the director and the characters leave the stage work up a scenario for rehearsal, and the second occurs when there is a mishap and the curtain accidentally descends and gets stuck (one assumes that the audience who remain in their seats hear the sounds of a frustrated director haranguing the stage hands behind the curtain). This is what the Naturalists called a “slice of life.” The audience should feel as if they are seeing real life.

And into this hyper-realistic world walks a group of fictional characters, whose very identity revolts against the realistic contract. Indeed, Pirandello called for the characters to be wearing stylized masks indicating the main characteristic of their archetype (one of those authorial stage directions rarely honored in productions, but nonetheless an interesting insight into Pirandello’s thinking). So: for the father, a mask of remorse; for the stepdaughter, revenge; the mother, sorrow; and so forth.

But there are two other nonrealistic aspects that are easy to overlook, but crucial to understanding the vertical plot. The first is the audience itself. Despite the fact that the audience is sitting in the same theater in which the actors and director are rehearsing—that there is a one-to-one correspondence between the “setting” of the play and our own reality—neither the actors and director nor the characters can see us. There is no moment when an actor acknowledges our presence, or directs a line or even a look in our direction. We share the same space and the same time, but the play and the audience exist in separate “levels of reality.” We are invisible observers.

The second breach of realism occurs in Act Two, when they are getting ready to rehearse the critical scene at the brothel, where the Father almost/not almost (more on that later) has sex with his Stepdaughter. In order to play that scene, they need Madame Pace (PAH-chay, meaning “Peace” in Italian), the woman who runs the hat shop that doubles as a brothel. The problem is that the (Offstage) Playwright did not make this character part of his play, otherwise she would have arrived with the rest of the Six Characters. The Father solves the problem: he borrows the hats and coats of the actresses and puts them on the stage “here and there on the pegs and hangers.” Questioned, the Father explains, “If we set the stage better, who knows whether she may not be attracted by the objects of her trade and perhaps appear among us.” And then he shouts, “Look! Look!” and upstage Madame Pace suddenly appears in the flesh. The actors and director totally freak out, and the Father calms them by saying, “Why should you wish to destroy this prodigy of reality, which was born, which was evoked, atracted and formed by this scene itself?…A reality that has more right to live here than you have…” So Madame Pace has been brought into existence by the creative act of constructing her environment and imagining her into existence.

This is a re-enacting of a story we have seen as long ago as the Book of Genesis, in which God creates humankind’s environment—the heavens and the earth, the water and vegetation, the birds and fish and animals—and then, only then, after the entire world has been created, is a human being born. Evoked. Brought into being by God’s act of imagination.

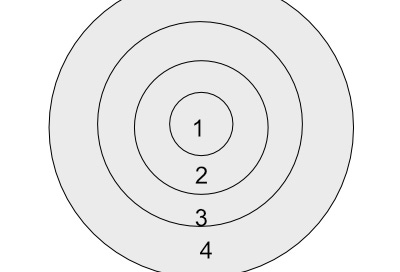

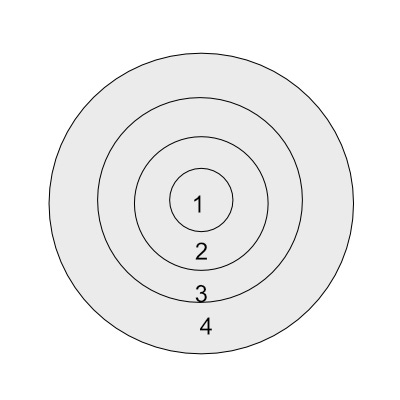

At this point, it is necessary to create an image of the world Pirandello has brought to life in this vertical plot, one comprised, like a Russian doll, of a series of embedded levels of reality:

Level 1: Madame Pace

Level 2: The Six Characters

Level 3: The Members of the Theater Company, and the (offstage) Playwright who created the characters

Level 4: Luigi Pirandello, and the Audience

What intrigues me about this is that each level is brought into being by an act of imagination undertaken by the next level higher. So: Madame Pace (Level 1) is brought into being by the creation of her environment by the Six Characters (Level 2); The Six Characters (Level 2) and Madame Pace (Level 1) are brought into being by an act of imagination of the offstage Playwright (Level 3); the Theater Company and the Offstage Playwright (Level 3), the Six Characters (Level 2), and Madame Pace (Level 1) are brought into being by an act of imagination by Luigi Pirandello and by the Audience (Level 4).

Which leads inevitably to the question: is there a Level 5? Is there a playwright who imagined us, the members of the audience, and who has imagined the story we are enacting? And in addition, are we being watched by another invisible audience, in the same way Level 3/2/1 is being watched by the unseen audience of Level 4?

Of course, none of this will be consciously registered by the audience while they watch the play. They may be as amazed as the Actors by the appearance of Madame Pace, especially if her appearance is sudden and magical, but the metaphyical implications will likely not appear until long after the play is over, if then.

Nevertheless, once you recognize this structure, then the Horizontal Plot not only makes much more sense, but actually becomes extraordinarily powerful.

More on that in “Six Characters in Search of an Author (Part 2): The Horizontal Plot,” which I will write as soon as I can. Until then, you might ponder on the implications of a Level 5…

Is there a Level 5? Is there a playwright who imagined us, the members of the audience, and who has imagined the story we are enacting?

I might have given more time to this answer, but I am gonna trust my immediate reaction. The answer is probably yes, but he or she is not in evidence. Were this a book, as the reader, we would hear the story told (a narrative) through that person. But, theater (stage) hopefully removes that narrator (creator) and allows us audience to have a more direct experience in the showing of the events that constitute the story. The actual playwright who authored the work we watch does exists, but is not made evident to us in the experience. (Unless you want to count the Playbill.) We know he or she exist or the work itself would not exist. But, they have no reference within stories told in action of the characters mentioned. And each of those, I presume, are seen and exist, except the offstage playwright - who is given direct reference (mention.) The work's originating author has no such reference except on the marquee and playbill.