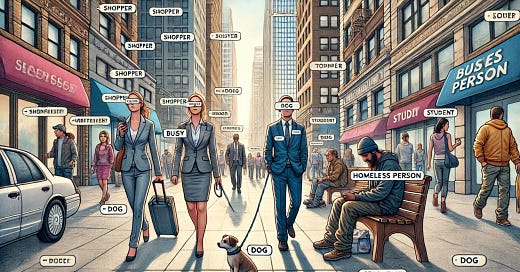

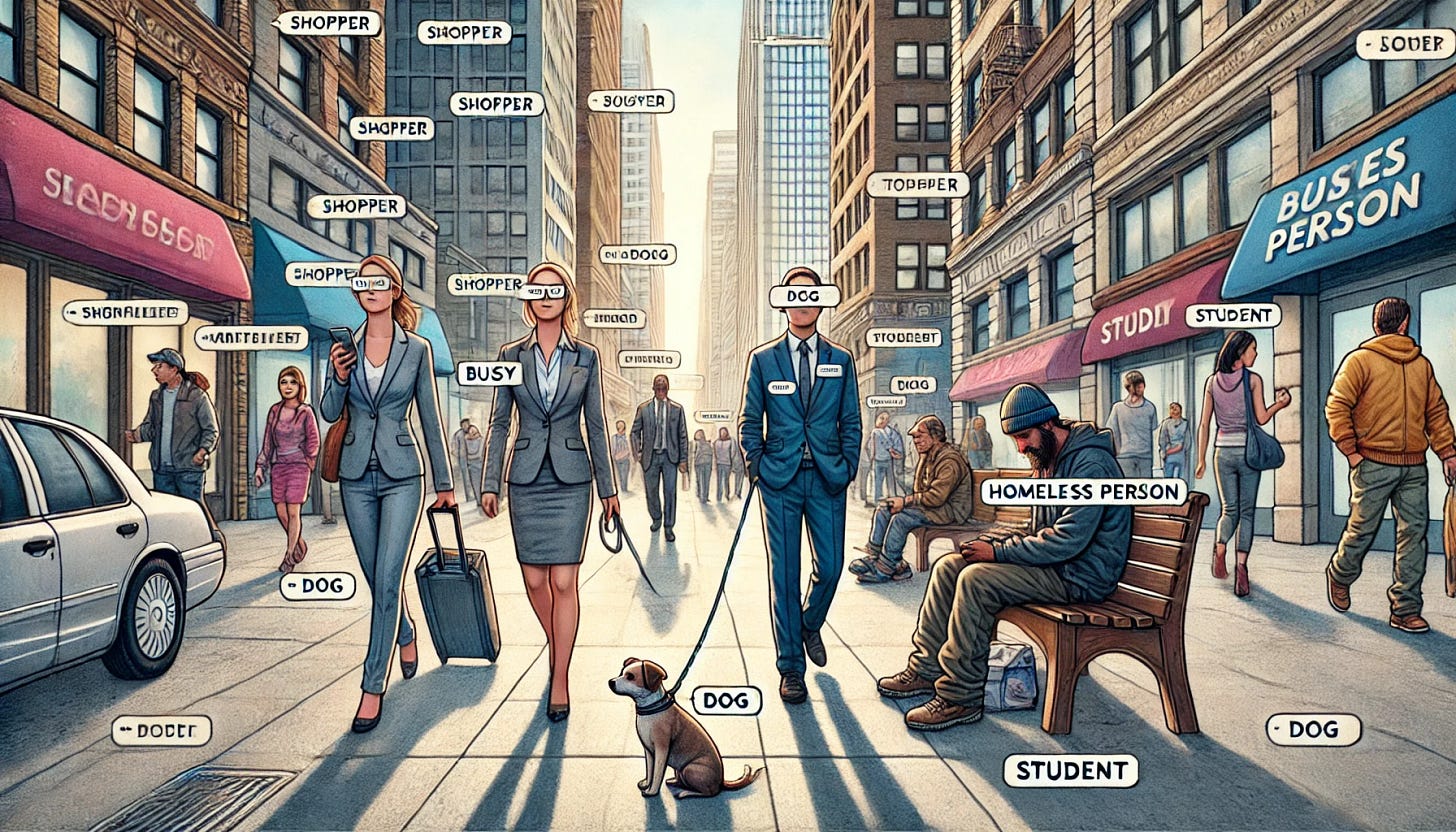

[image generated by AI, which is why many of the labels are random.]

I’ve been reading (and enjoying) J. F. Martels’ book Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice: A Treatise, Critique, and Call to Action (the ebook is currently available for Kindle for $1.99), and also listening to Martel’s podcast that he does with Phil Ford, which is called Weird Studies. (I’ll likely discuss both in greater depth in future posts.) In Chapter 3: Terrible Beauty, Martel refers to philosopher Henri Bergson’s 1900 essay Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic, in which Bergson says that, in order to survive in day-to-day life, it is necessary for our mind and senses to focus our attention on “the utilitarian side of things in order to respond to them by appropriate reactions: All other impressions must be dimmed or else reach us vague and blurred.” He goes on, “we do not see the actual things themselves, [but mostly] confine ourselves to reading the labels affixed to them.” This has been scientifically shown to be true—the sheer amount of information with which the world bombards our senses and our mind would be overwhelming without the ability to filter out that which is unimportant for the moment. Filtering is a survival mechanism.

Language helps us with this process, Martel continues, paraphrasing Bergson, because “language is always about the general and never about the specific. The word cat can apply to animals fitting a certain anatomical description, but in applying it unreservedly to any one creature, we lose what is singular in that particular cat, the spark of pure difference that sets it apart from everything else.” Bergson asserted that, “if we could see the world directly, there would be no need for art.”

Seventeen years later, the Russian Formalist theorist Viktor Shklovsky published an essay called “Art as Technique,” in which he asserted something similar to Bergson but from a slightly different perspective. “Art exists,” Shklovsky writes, “that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony.” Or, to go back to the analogy of the cat, to make just any old cat into a particular cat through the removal of as much of the filter as possible in order to allow us to see and experience not just the label but the “thing in itself” (to borrow Kant’s famous phrase).

Isn’t that also what love does? Isn’t falling in love the gradual process of coming to fully see another person in all their miraculous particularity, and then reflecting what you see back to that person, so that they, too, can see the beautiful particularity that is them? I’m reminded of a lyric from Paul Simon’s song “Graceland” in which he’s writing about a breakup: “She comes back to tell me she's gone / As if I didn't know that / As if I didn't know my own bed / As if I'd never noticed / The way she brushed her hair from her forehead.” That song’s narrator had gone beyond label-sight and noticed a unique way his partner had of doing a small, seemingly insignificant thing, and he’d valued it. (One wonders whether the relationship had fallen apart because the narrator had noticed, but failed to reflect it back to his partner. But I digress.)

The poet Mary Oliver, when her long-time companion, M. (Molly Malone Cook), passed away, wrote:

It has frequently been remarked, about my own writings, that I emphasize the notion of attention. This began simply enough: to see that the way the flicker flies is greatly different from the way the swallow plays in the golden air of summer. It was my pleasure to notice such things, it was a good first step. But later, watching M. when she was taking photographs, and watching her in the darkroom, and no less watching the intensity and openness with which she dealt with friends, and strangers too, taught me what real attention is about. Attention without feeling, I began to learn, is only a report. An openness—an empathy—was necessary if the attention was to matter.

(You can read more about this on Maria Popova’s blog The Marginalian, which I can’t recommend highly enough.)

When I moved to New York City to get my doctorate in the late 1980s, the problem of homelessness had become severe in the wake of Reagan’s policies regarding mental illness. At first, my heart nearly broke every time I would meet their eyes, or see some detail scrawled onto the cardboard appeal at their feet, or some personal item that spilled from their grocery bag. But it didn’t take very long for me to develop the filter that I found necessary to go about my daily business. I just didn’t have the time or money to help, and the emotional cost of openness and empathy was taking its toll. And so gradually, they stopped being individuals, and instead acquired the label “Homeless Person,” allowing me to see them without seeing them, and so more easily pass them by. The miracle of someone like Dorothy Day, who devoted her life to actually seeing and hearing the destitute at the shelter she co-founded and operated on the Lower East Side of New York. Her willingness to see, to reflect back, to maintain an openness and empathy over time is one of the things that has led to the Catholic Church’s consideration of her for sainthood.

The philosopher Simone Weil equated attention with prayer, and wrote “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity” in that it “presupposes faith and love.” (Learn more about Simone Weil on Stephen West’s podcast Philosophize This!, which I also recommend highly.)

If art, then, slows down our perception by removing the label-making filter and, by so doing, helps us to see, hear, and feel the sublime specificity of life—in other words, “makes the stone stony”—it is helping us to fall in love again with the world and with the possibility of seeing each other. It makes it possible for us to be astonished, which Martel defines as being “caught unawares by the revelation of realities denied or repressed in the everyday.”

One might say that art shows us the way life brushes its hair from its forehead.

Martel’s title contrasts art with “artifice,” a term he draws from James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. I will write more about artifice in the next post.