Dear Readers—I hope you had a lovely Christmas, for those who celebrate. We had accumulated about 5” of snow, and our street was filled with people with Christmas lights blinking and glowing.

I wrote more than I anticipated thanks to a sudden burst of writing energy shortly after I sent last week’s newsletter, so there is actually several long posts for your enjoyment.

My longest post had an equally long title: “Alan Jacobs, Ross Douthat, Margo Jones, Tony Kushner and the Fate of (Pop) Culture.”

A sample:

“I’ve followed Jacobs’s inclinations, revisiting the classics of theater, novels, philosophy, music, poetry, and visual art. And it’s been great, and that’s great for me as an arts consumer, but as Jacobs himself admits, it is pretty awful for the artists. And ultimately what is bad for the artists is bad for our culture, and what is bad for the culture is bad for our society…Is it hard to find great contemporary art in our fragmented, algorithmic culture? Sure. So what? Stop being like baby birds in the nest with their beaks wide open crying out for some Mama Bird to bring the worm of great art back and shove it down their little throats. Do some damn work! And when you find it, celebrate it–tell your friends, write on your blog. That’s what social media ought to be good for–telling the world. Yes, sure, read Eliot and Auden and Mann and Dostoevsky, AND look for today’s incarnations and bring them to the attention of the world.”

Read the whole thing here.

I then stumbled on another Alan Jacobs post, “The Work Itself,” about which I wrote:

It seems to be an Alan Jacobs day! His post called “The Work Itself,” about the difference between being an influencer and doing a job, is excellent. For me, it is coinciding with my current reading of Matthew B Crawford’s Shop Class as Soulcraft and The World Beyond Your Head, _as well as Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman.

For the artist, the work as an end in itself ought to be your entire focus. Yet in theater and film, too much attention is given by professors and the media to “success” defined by fame and fortune, both of which are worthless to a true artist. Do the work.

The theater critic for the LA Times, Charles McNulty, wrote “The theater’s rich intellectual inheritance serves as a buffer to society’s recrudescent stupidity.”

I’m thinking about having a t-shirt made emblazoned with “A Buffer to Society’s Recrudescent Stupidity.” Perhaps with, in parenthesis: “look it up.”

Erik Hoel, in a Substack article entitled “How the MFA Swallowed Literature: On the Total World Domination of Workshopped Fiction,” wrote:

“…things do seem to have changed in literary fiction, and you don’t have to go back far to see it. The year? 2006. The people? Those the novelist Garth Risk Hallberg called the “Conversazioni group” for their joint attendance of a 2006 literary festival in Italy (called Le Conversazioni), interesting fragments of which have ended up on YouTube. The members of the group were Zadie Smith, Jonathan Franzen, David Foster Wallace, and Jeffrey Eugenides. All were in their thirties or forties: Smith (31), Franzen (47), Wallace (43), Eugenides (46). All were public-facing artists, and their debates were on the form and function of writing itself: who could forget the term “hysterical realism” or “contract vs. status” novels?”

At first I wrote a response that dittoed for theater his criticism of creative writing MFA’s, but then I deleted it because in the middle of the article I saw something else: longing for a public conversation of ideas. I wrote, in a post entitled “Where Are Our Prophets?” that really needs more development:

But what I find interesting is, in the midst of a lamentation about the deadening effect of the MFA on literary fiction is this seeming longing for, well, a conversation like the one in Italy, like the public-facing conversations had by Franzen, Smith, Wallace, and Eugenides.

I have certainly felt the same about theater. Where are the artists who are discussing ideas, values, principles? Where are the manifestos? They seem missing, and I think it is because large theaters don’t want anyone to rock the boat, protesting that it’s hard enough to keep things afloat without dealing with Big Ideas and rabble rousers. What we have instead are kvetchers.

The theologian Walter Breuggemann, in his classic book The Prophetic Imagination said there were two elements of prophetic speech: strong criticism of the status quo, and an inspiring vision of a new world that is possible. Theater seems to have only the first part; we’re in desperate need of second.

I’ve started reading critic Richard Hoftstadter’s 1964 classic Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, which sounds more like it was written yesterday rather than sixty years ago. He writes:

“The common strain that binds together the attitudes and ideas which I call anti-intellectual is a resentment and suspicion of the life of the mind and of those who are considered to represent it; and a disposition constantly to minimize the value of that life.”

That seems to be where we’re at.

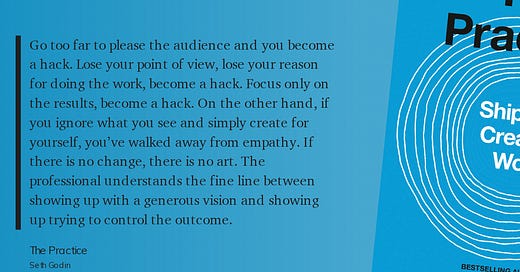

Finally, a quotation from Seth Godin’s book The Practice. He describes a fine line that I think the best playwrights and artists understand instinctively.

Thanks for reading. If you want to see these ideas as they appear, go to ScottWalters@micro.blog.

Have a Happy New Year!

Scott