[Thank you for your patience. I’ve been down with a cold, which accounts for the delay in writing Part 2 of my “On Gatekeepers and Critics” series. Bear with me.]

But before getting back to that essay, I need to once again address Fergus Morgan, writing on Substack at “The Crush Bar.” This morning, in a post entitled “Sorry, I'd rather pay £9.99 to see Dune: Part Two than £99.50 to see Hamilton,” Morgan once again tries to have it both ways by appending the subtitle “I know it is very, very wrong to reduce art to numbers, but I am going to do it anyway to make a point about affordability, access and big worms.” Y’all may remember that I recently felt it necessary to address another post by Mr Morgan in which he called for theater people be less mean on the internet, by which he meant saying out loud that the theater system is dysfunctional. I addressed it here, and I hope you will remember both of these posts when my call for more and better critics finally comes out.

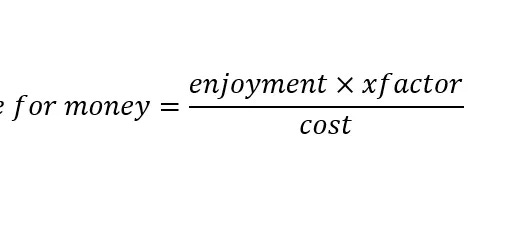

The irony, at least as far as today’s post is concerned, is that Mr Morgan and I agree on the central point: theater is too expensive. But as seems to be usual, instead of questioning the underlying artistic and financial decisions of touring productions, he instead creates an absolutely absurd mathematical argument to make him feel better about preferring Dune to Hamilton. And he claims it is universally applicable to boot! Here it is:

Time for some maths. You can use this formula to generate a value for money metric for anything, from sci-fi movies to sung-through musicals to reading this newsletter:

So, Dune: Part Two is (5 x 3)/9.99, which equals 1.5. Hamilton is (5 x 5)/99.50, which equals 0.25. According to my calculation then, Dune: Part Two offers better value for money. You can set your own bar for an experience to clear: the tighter you are, the lower it will be; the flusher you are, the higher it will be. Mine is probably about 1. Dune: Part Two passes the test. Hamilton fails it. Even if I chose the most expensive cinema ticket in Edinburgh (£17.65 in the fancy Everyman where you can get a G&T brought to your seat) and the cheapest theatre ticket (£30), Dune: Part Two still wins.

Even if we grant the idea that “value for money” is a reasonable way to evaluate one’s entertainment choices, and setting aside the otherwise glaring fact that the cheapest seats for the Taylor Swift “Era’s Tour” concert were £650 and she sold out 90,000-seat Wembley for eight performances… well, we can’t really set all that aside, because it’s germane. But regardless, Mr Morgan’s equation is rigged. There is almost no way that Hamilton can compete, using that equation.

Let’s pretend that Dune: Part Two was absolute dreck, so the “enjoyment factor” was the lowest possible except for the worms: 1.5. The so-called “xfactor” in the equation is defined as follows:

There is educational value (did it teach you anything?), there is spiritual value (did it make you a better person?), there is aesthetic/social value (did you get a good photo for your Instagram?), and there is a scarcity value (I can and will go see Dune: Part Two again, but the Scottish premiere of Hamilton is a one-time thing).

Let’s pretend that Dune: Part Two once again failed utterly in all these categories, scoring a 2 (it get’s a point because you can easily go back and see it again). So in this sample, the experience of watching Dune: Part Two was horrible except for the worms (1.5): it wasn’t at all enjoyable, it didn’t teach you anything, it had no spiritual or aesthetic/social value, but you can go back and see it again. How does that math work out?

(1.5 x 2)/ 9.99 = 0.3

Even giving Hamilton the highest marks, as Mr Morgan does, results in a lower score of 0.25. (Let’s do Taylor Swift now, giving her top ratings: (5 x 5)/650 = 0.038. I suspect you’d have a hard time finding anyone in Wembley wishing they’d been sitting in the comfy seat next to Fergus for Dune: Part Two.) And Mr Morgan insists that his value-for-money breaking point is 1.0, so there’s no way Hamilton is ever viable, even at 1/3 the price.

I’m taking this equation more seriously than it deserves. And I get it—in order for me to shell out the required amount to see Hamilton in New York, the experience would have to have lifted me bodily into heaven and placed me on a cloud sitting next to Harold Clurman and Zelda Fichandler. But the point I want to make is that this level of superficiality when it comes to making an argument about, well, anything simply defeats the purpose through its absurdity. And it’s nor just Mr Morgan—this is the same sort of nonsensical arguments that are used to argue for more government funding for the arts: “the arts “generate” X number of dollars for the economy, or “just give the nonprofit arts sector $500M for five years and it will get us through this rough post-COVID patch.” These are houses of cards that are easily knocked over by a slightest gust of mathematical wind. Americans for the Arts, for instance, has been making these sorts of arguments for years—over and over again, to absolutely no avail. Government funding continues to shrink in real numbers. I wrote about this in Chapter 1 of Building a Sustainable Theater:

In 1980, Ronald Reagan cut the NEA budget to $143M; now in 2024, Joe Biden requested $211M…As far as spending power is concerned, compared to Reagan, Biden looks like a skinflint: in 1980, $143M had the same spending power as $561M today, more than two-and-a-half times Biden’s proposed appropriation.

Let’s put this another way: $4 in 2024 is about equal to $1 in 1980. So if our current NEA budget was converted to 1980 dollars, it would be less than $53M. Looked at this way, Reagan—Reagan!—was Santa Claus.

Anyway, it is time for somebody to come up with better arguments to support government funding of the arts, or at the very least stop repeating these embarrassingly bad ones. At the rate we’re going, we’re going to wind up having to pay the government for the right to do theater (don’t give them any ideas). [Here’s one: vouchers. Everyone with an adjusted gross income of under X dollars receives a government voucher for a certain amount that can be used at a nonprofit arts organization or museum. They can use the voucher, or sell it to someone else. I have no idea whether this makes any sense (I just made it up off the top of my head), but at least it has the value of breaking us out of the usual arguments, and would be a income-based model that subsidized the poor instead of the wealthy.]

Alternatively, we get out of the lobbying business, take control of our business model, and figure out a better way to make theater sustainable. That’s my preference.

What we can’t do is use stupid math tricks to make either case.